Wildlife Rehabilitator Tends, Patches or Dispatches Nature’s Wounded

- Patrick Durkin

- Aug 6, 2025

- 5 min read

You name the critter, and Mark Naniot has probably uncorked a can, jar, cup or bottle from its head during his nearly 40-year career as owner/director of the Wild Instincts rehabilitation center in Rhinelander.

Whether it’s a skunk lapping peanut butter, a squirrel licking yogurt, a bear chomping pickles, or a raccoon vacuuming corn kernels, Naniot has spared it from an agonizing death after it went headfirst for a litterbug’s leftovers.

In other cases, Naniot has saved ducks and turtles from garroting themselves by swimming through plastic six-pack rings that once held beer or soda, wedging their neck or body into these indestructible yokes. In one case, a young painted turtle slid itself into a six-pack ring and kept growing. Two years later, its shell resembled a narrow-waisted violin, with the plastic rings still draped over its posterior. In fact, the plastic looked like it just rolled off a soda-canning line.

Discarded fishing line also snags and kills unsuspecting wildlife. In one case, Naniot showed up in someone’s backyard after an immature bald eagle tangled itself in discarded fishing line. The eagle was still alive when Naniot was summoned, but then got stuck high up the utility pole as the monofilament tangled tightly into the transformer’s wiring. By the time Naniot arrived, the eagle hung dead after getting electrocuted.

In other avoidable accidents, people have walked into the Wild Instincts center with a chickadee or chipping sparrow in one hand, and an iced-down sandwich bag in the other, protecting a severed wing. They ask if Naniot can reunite the agitated bird with its wing.

Whether it’s jars or cans, above, or plastic rings from a six-pack, below, litter often kills wildlife across Wisconsin. — Photos courtesy of Mark Naniot, Wild Instincts

No, but perhaps the person learned a painful lesson about hanging flypaper on his open porch. Now he knows flypaper and glue traps catch bats and birds as readily as they do flies, gnats and mosquitoes.

And even when people do things to wildlife they’d never try on a pet or child, they call Naniot on Monday morning to undo their recklessness. “Hey Mark. We found this duckling Friday. We kept it all weekend for the kids. We let them play with it and take a bath with it. We have to go to work today and we’re on our way to school to drop off the kids. No, it hasn’t eaten anything since we found it, but here you go. Thanks! Gotta run!”

Naniot shared these experiences Aug. 2 at the Trees for Tomorrow education center in Eagle River during the annual convention of the Wisconsin Outdoor Communicators Association. He said Wild Instincts treats about 125 species of animals annually, ranging from bears to deer, eagles to hummingbirds, and otters to weasels.

“We work on every wildlife species allowable by state and federal law,” Naniot said. “The only two animals we can’t work on by law are skunks and wolves. Wolves have become too political, and skunks have been off limits since the 1940s when they were Wisconsin’s top rabies-vector species. Bats are now the state’s No. 1 rabies-carrying species, while No. 2 is raccoons, and No. 3 is skunks. We’ve always worked on bats and raccoons, but we’ve never worked on skunks. The most we’ve done with them is pull their head from jars. That usually ended well, but not always.”

Naniot tries not to judge inconsistencies in policy and people. He focuses on his “patient” to give it a second chance at life, but concedes his greatest challenge is working with the public.

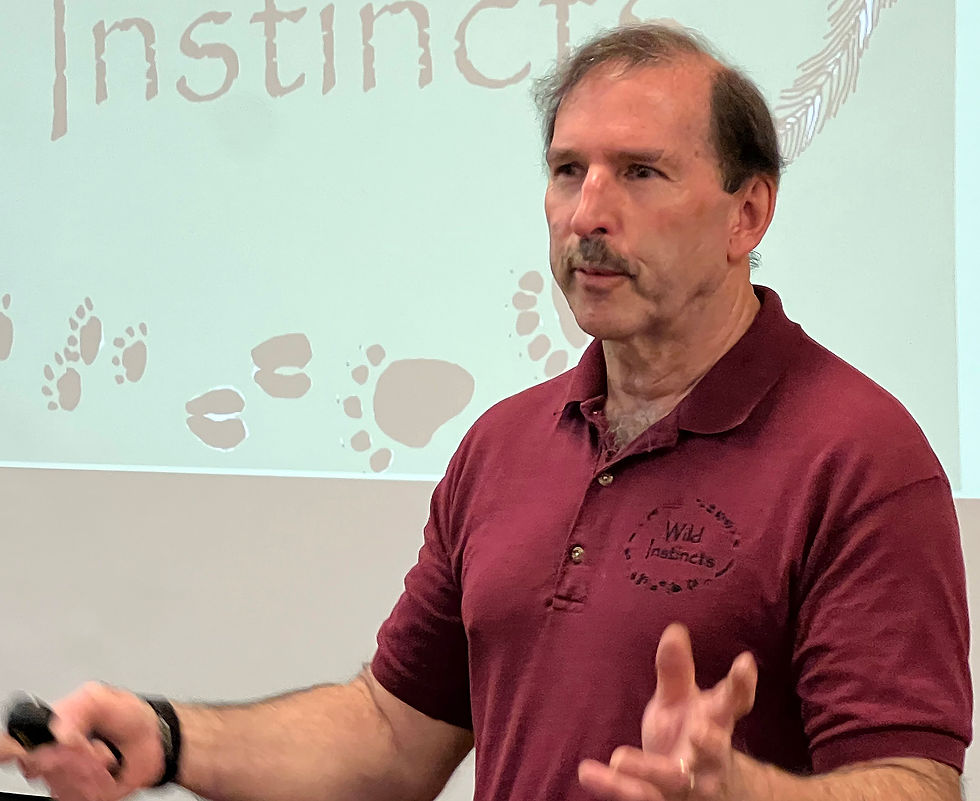

Mark Naniot, owner/director of the Wild Instincts rehabilitation center in Rhinelander, addresses the Wisconsin Outdoor Communicators Association at its annual conference in Eagle River. — Patrick Durkin photo

“We see the good side of people, but a lot of our job is trying to cure problems they create,” he said. “We’ve had people drive a little pink mouse two or three hours in one direction so we can take care of it. We’ve asked other people to bring us an animal, or meet us halfway or partway, and they’ll say they can take it to the end of their driveway.”

Either way, Naniot recites endless ways people of all persuasions harm wildlife. Therefore, hunters shouldn’t feel persecuted when asked to shoot copper bullets so eagles don’t suffer lead poisoning when scavenging a deer’s blood-clotted entrails. And anglers shouldn’t be offended when asked to cut discarded fishing lines into chunks so shorebirds don’t hog-tie themselves when foraging. And trappers shouldn’t feel insulted when a violator gets caught and makes the news for targeting raptors with an illegal dry-ground set.

“Humans are one of main causes of problems that wildlife experience,” Naniot said. “It’s a never-ending challenge. Some people have good backgrounds with animals, maybe in farming or as longtime pet owners. But how many of us know cow’s milk is 26% protein and 26% fat, while bear cubs require milk that’s 30% protein and 50% fat? You can’t feed bear cubs and calves the same milk and expect happy endings.”

In other cases, Naniot has rescued a great-horned owl stuck in the netting of a soccer goal, and euthanized a white-tailed buck whose antlers snagged a volleyball net. The buck thrashed so hard while trying to escape that it fractured its skull, turning one antler 180 degrees.

Fixing injuries caused by screw-ups, inattention and fluke accidents can be difficult, but they’re not as maddening as repairing acts of cruelty. Naniot sees no end to malice, either. He’s euthanized eagles peppered with shotgun pellets and ospreys with dead legs caught in illegal traps. And he once removed a 4-inch nail someone pounded through a box turtle. In yet another case, he euthanized a snapping turtle after youths fractured its shell, shattered its jaw and destroyed one eye by battering it with a skateboard.

More common, though, are turtles crushed by motorists, sometimes intentionally. In fact, studies in Ontario, Kansas and South Carolina found that roughly 3% of motorists who see turtles on roads or roadside shoulders swerve to hit them.

Pat Conroy’s 1976 semi-autobiographical novel “The Great Santini” even recounts his father repeatedly positioning their car to “expertly snap the animal’s shell, which made a scant pop like the breaking of an egg. It kept him from getting bored; it kept him alert. He always did it when his wife and children were asleep.”

When possible, Naniot helps such injured turtles, applying epoxy and fiberglass mesh to patch holes and fuse shell fractures. If the turtle survives, the patch eventually frays and falls away.

As a longtime hunter and angler, Naniot knows nature can be relentlessly cruel and forever indifferent. He can’t do anything about that.

He expects more from people, but suspects they’ll forever bring disappointment to Wild Instincts’ door.

Comments